Eye For Film >> Movies >> Oliver Sacks: His Own Life (2019) Film Review

Oliver Sacks: His Own Life

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

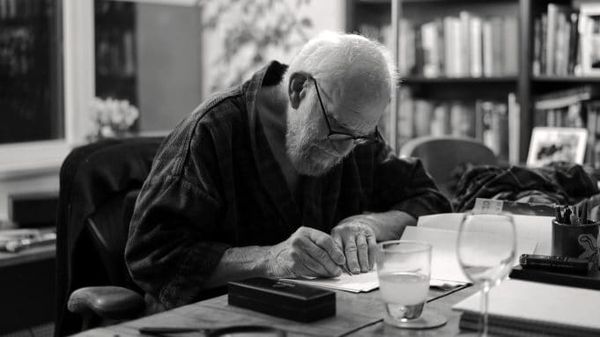

On analytic days – and Monday, when the first scene in this film was shot, was an analytic day – Oliver Sacks had a Freudian mug to drink out of. He shows it to the camera, beaming like a small boy. It’s a simple thing but Sacks understood, perhaps better than most, how little things can make a person happy. Filmed in the period leading up to his death, this documentary reflects on his work as a doctor and a writer (“in important ways they blend together,” he says) and on a life that was often lonely, one that he survived partly through his ability to find joy in unexpected places.

Director Ric Burns is well known for his histories, both personal and national, and in Sacks’ story he finds something of both. It’s the story of a boy born into a respectable home – both his parents were doctors – and blessed with opportunity to match his keen intelligence, who nevertheless found himself an outsider and who championed the cause of outsiders throughout his life. Misunderstood and sidelined for a long time by the medical establishment, he nevertheless achieved widespread public acclaim, both these things perhaps stemming from his willingness to make the field of neurology accessible and his assertion that what a doctor needs most is empathy.

The other side of Sacks’ empathy was his natural likeability – an asset he didn’t make use of for a long time due to his natural shyness, but which shone out of him in his later years. It would be practically impossible to make a dull film about this man and it’s arguably difficult to make a balanced one. Though Burns takes note of the criticism Sacks faced, notably the claims that he put personal glory ahead of ethics and that he exploited his patients, it’s not the evidence that prompts one to reject them – though it is present – so much as the inherent difficult of thinking badly of a man who seems to open, warm and engaging. A man who proudly shows the camera his periodic table bedcover and his collection of elements – one for each birthday – before declaring “If you doubt reality, drop tungsten on your foot.”

Sacks was a man very much shaped by the times through which he lived, the treatment of his schizophrenic brother Michael convincing him that there had to be a kinder way to deal with mentally ill people, whilst his experience of being gay in a profoundly homophobic society led him to take refuge first in bodybuilding and later in recreational drugs, pushing his body and mind to the edge again and again. It was when he eventually realised he had to get help, and started undergoing psychoanalysis, that he became fascinated by the brain and began to exert his own influence on the world. Here we move on from a period captured in still photographs to one brought to life in film, witnessing the famous awakenings that would later be dramatised in a film with Robin Williams, whom we see briefly talking with Sacks in another piece of archive footage.

Much like Sacks’ home, this documentary is a treasure trove full of interesting bits and pieces many of which could easily provide enough material for a film in their own right. Sacks’ most passionate contention was that helping people had to begin with trying to understand the whole of who they were, not just what was aberrant about them. Forewarned of his death from malignant melanoma, he worked hard to sum up his own life in words during his final few months, and this film provides a complementary perspective. It’s enriched by contributions from those who knew him, and from those, like Temple Grandin, who drew inspiration from his work; but it’s Sacks himself, reflecting on an injured leg, apologising for his “multisyllabic swearing” or, in his seventies, falling in love for the first time, who is its brightest jewel.

Reviewed on: 04 Mar 2020